To Sleep Perchance To Dream

“ay, there’s the rub; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come.”

Entering the basement of 28 Back Burton Terrace is an unexpected and very singular experience. More than just a basement it is something closer to the wardrobe entrance to Narnia; behind an unassuming door, down a narrow cobwebby flight of stairs lies a world of experience and ideas. With every passing exhibition a whole new universe opens up, one driven by the ideas of yet another artist who has stumbled upon our highly personal, and admittedly quite strange concept, and decided that they have something to contribute.

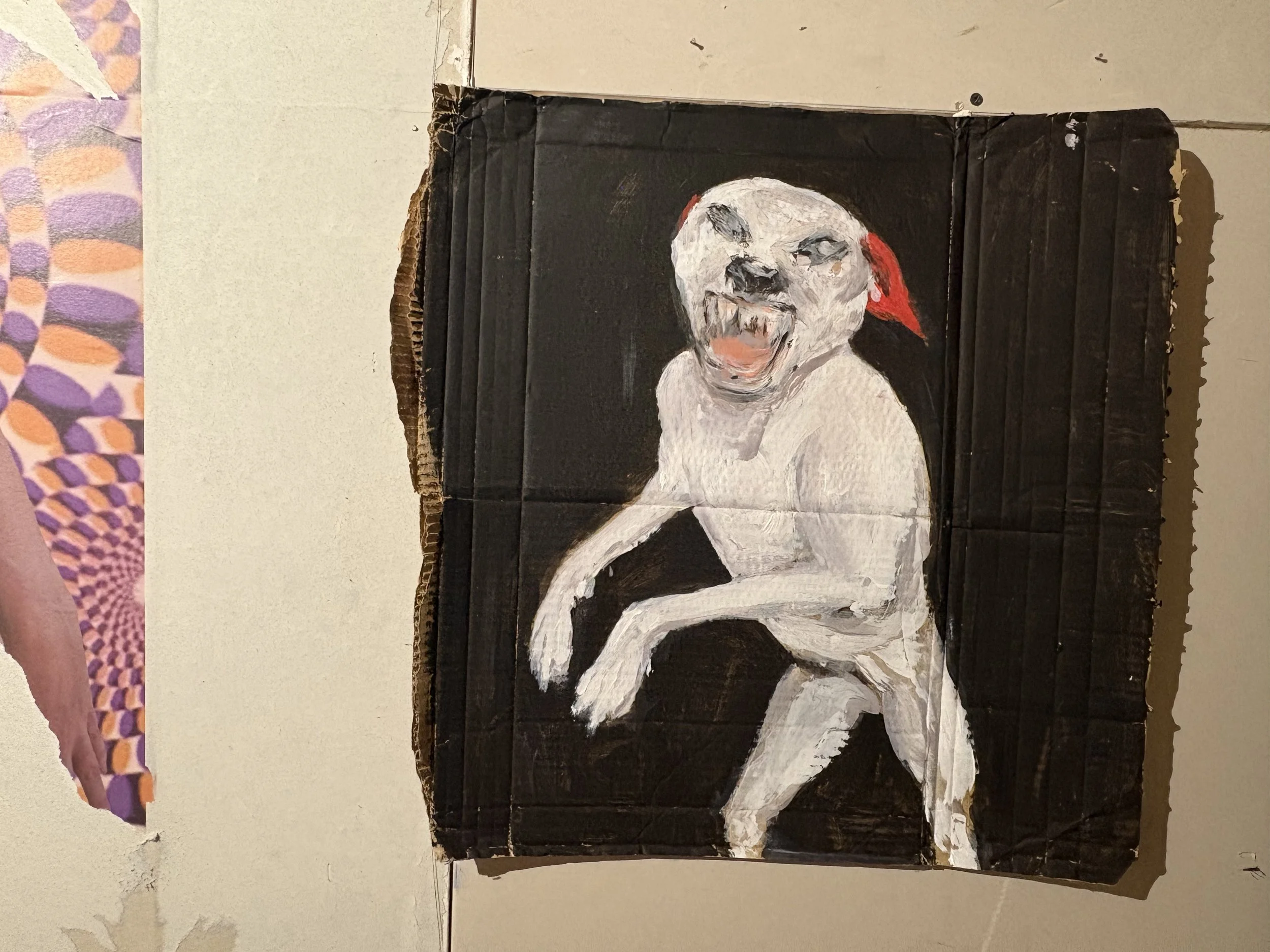

‘Tirweddau Dychmugol-Faesiol’ further blurs the boundaries between real and unreal, fact and fiction, waking and sleeping. Here, dreams break through into the waking world and the waking world impinges on dreams. A series of white dogs with red ears -‘Y Cwn (The Dogs)’- oversees the darkness of the rear space. Whilst one slyly watches the entrance another is foaming at the mouth as it rears up to meet the viewer and in the middle, the only one painted on canvas, appears to be in turmoil, flailing its head from side-to-side as though ripping a dog toy to pieces. These are images that are simultaneously cartoonish and nightmarish hovering against the dilapidated backdrop of ‘The Basement’.

Opposite, are three larger works. A central work entitled ‘Yn Y Castell (In The Castle)’ is a large monochromatic painting of something that looks like it could be Nike of Samothrace but with her head restored against a backdrop featuring a series of Doric columns, but of course this is a dream landscape in which everything breaks apart and remakes itself. There may be no context but there is always meaning.

To the left of this image is ‘Y Cwsg (The Sleep)’ and on the right ‘Y Marwolaeth (The Death)’. These two works stand like sentries guarding Y Castell, the remaining supports of the chopped out chimney breast bearing a visual resemblance to a pair of flying buttresses’.

In the front half of the exhibition space the mood is different. I am drawn back to a childhood memory, one of cheaply produced storybook compendiums printed in three colours, and I’m not sure why! The only explanation I can think of may be the pastel colour scheme and images that could have come directly from one of these books but distorted in the passage of time as they are pulled between the waking and dream states of the child mind as it makes its half century journey, mine not the artist, into adulthood.

In a corner, almost unnoticeable amongst the cobwebs and pipes of the electricity and gas meters is a strange untitled sculptural translation of what appears to be a head, a garbled transmission from another world, looking down on the scene below, watching, waiting, planning, maybe protecting? Like ‘Y Cwn (i)’ absolutely inscrutable in relation to its intentions.

On the chimney breast are two paintings that I initially mis-read and show my age. They could be paintings made of house mates in a student house. The titles ‘Y Tad (The Father)’ and ‘Y Fam (The Mother)’ reveal them to be the artist's parents in their youth, presumably made from old photographs. My own age based confusion stems from the bottle of wine on a book shelf, identical to shelves currently in use in my own bedroom, in the background of one of the paintings. In these images time has collapsed and what could be the present becomes the past.

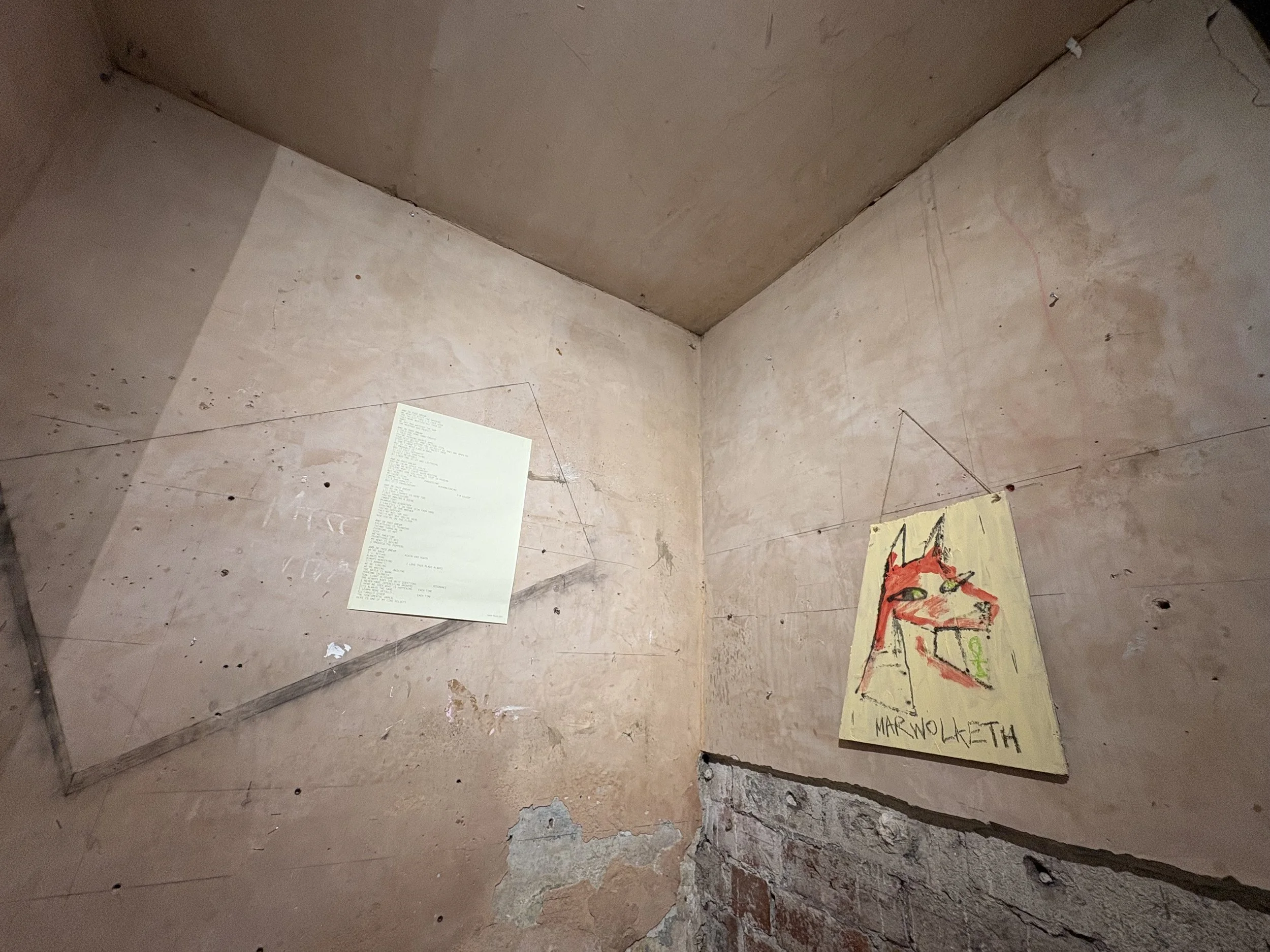

On the opposite wall a series of pennant shaped works on rough cut boards are hung amidst the decaying plaster and pipe work. Is this the subconscious telling stories…?

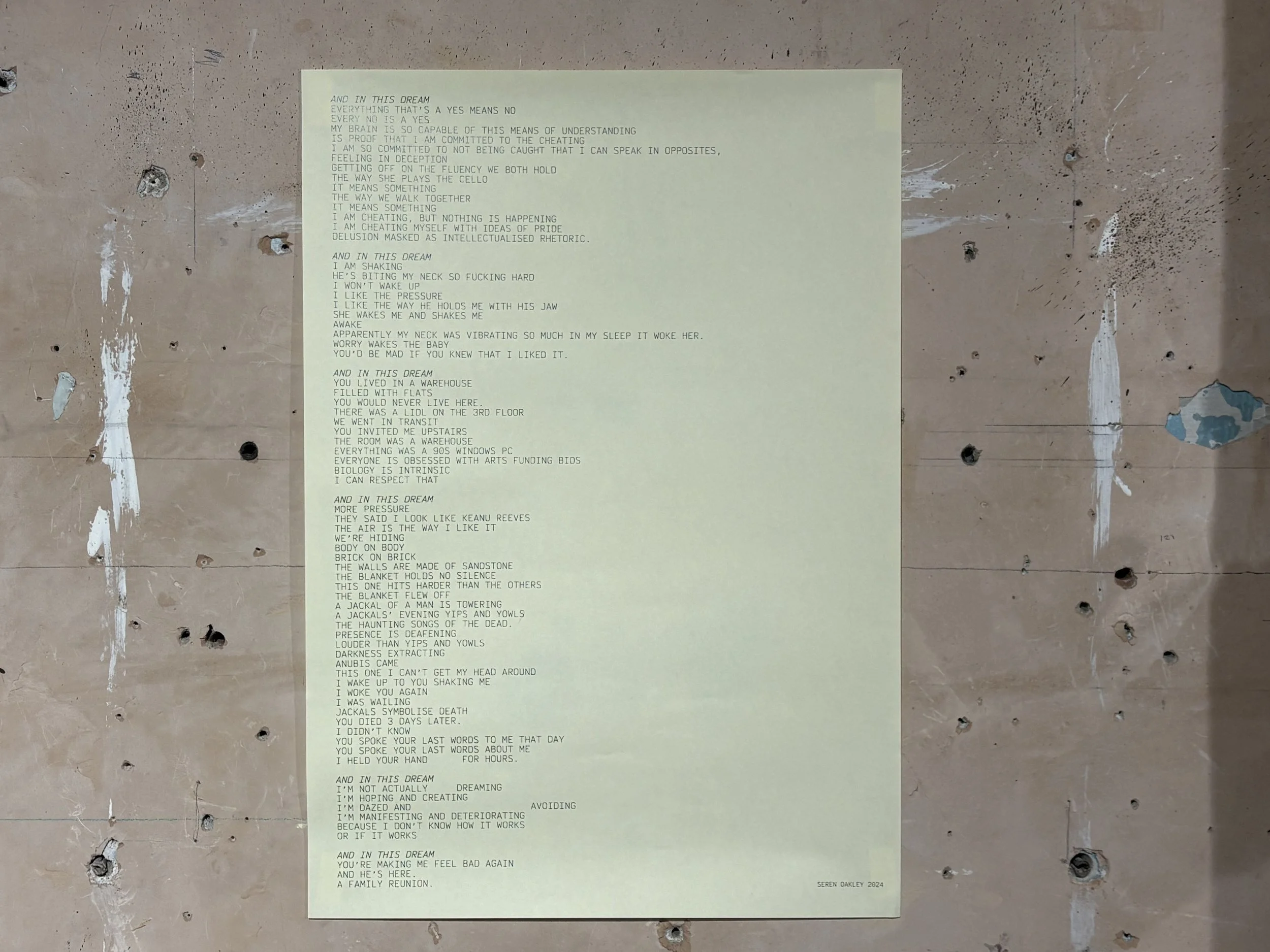

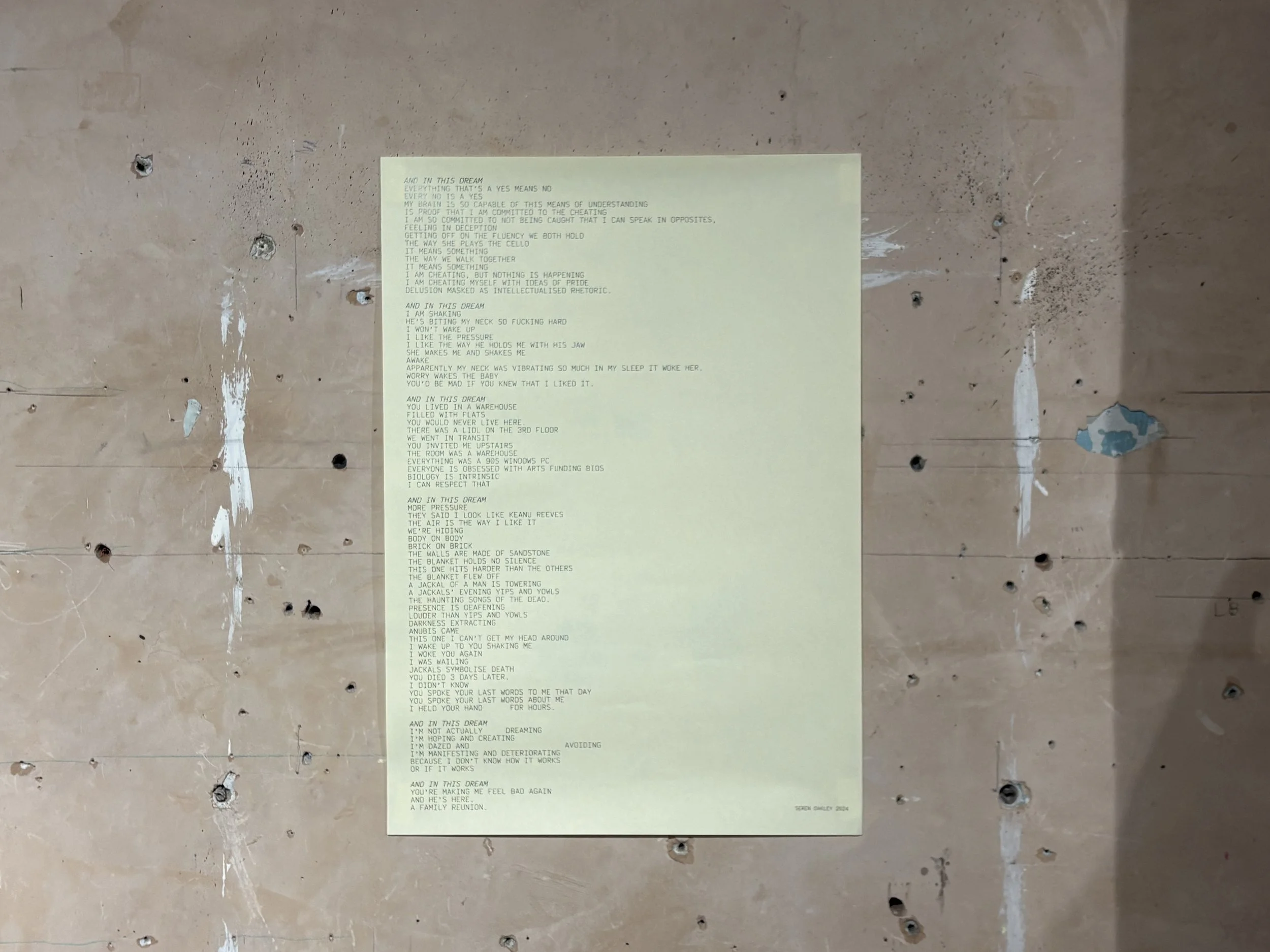

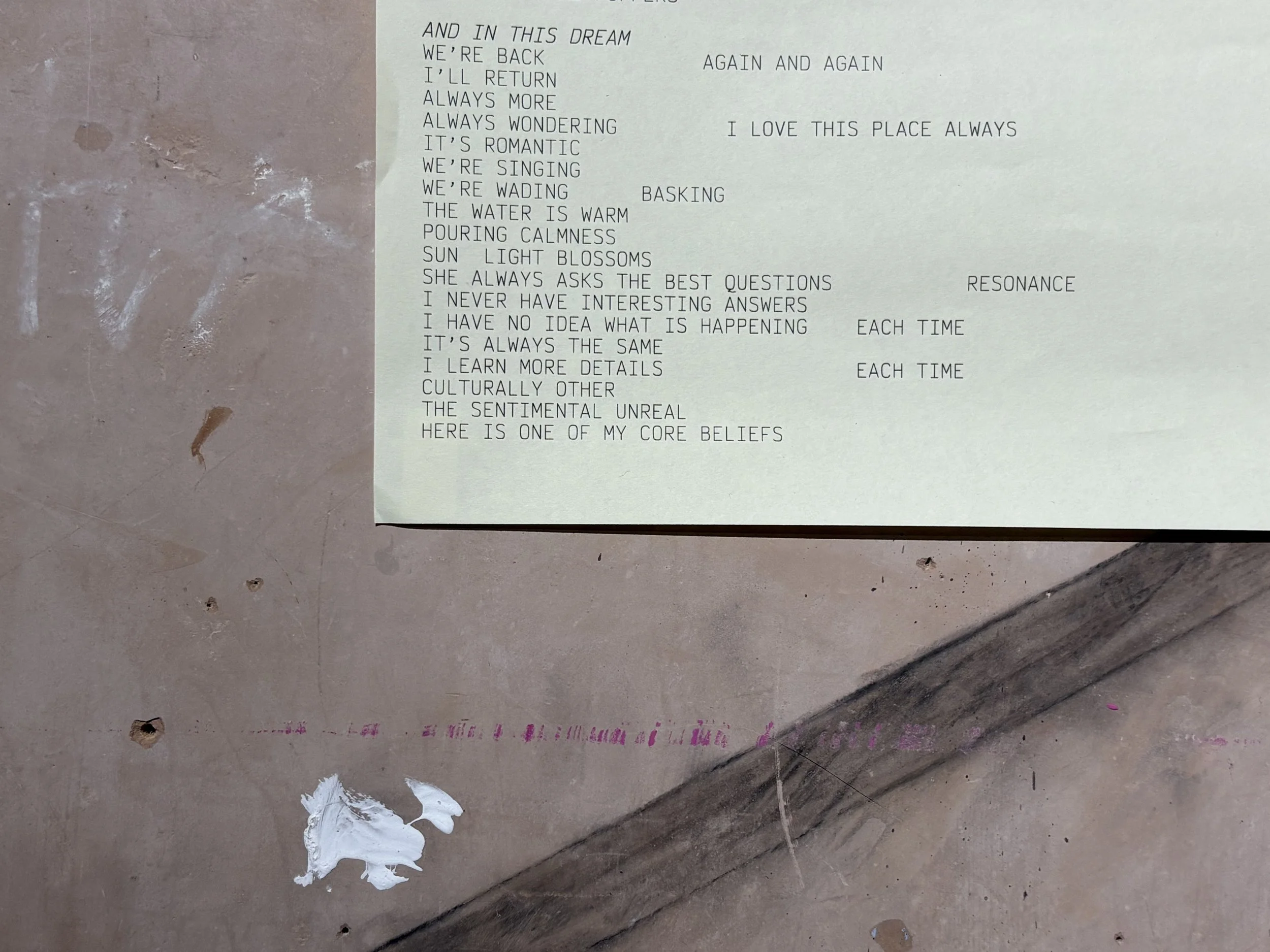

Elsewhere, two sheets of non-standard sized paper with an off white hue draw me back to childhood memories; a type of paper that my looks like something my Grandad used to have in his cupboard in the seventies and early eighties that would record the shape of objects placed on it, photogram style, when left in the sunlight for even a short length of time. On these two sheets are fragments of dreams, recorded as text that seem to form pieces of obscure poetry in which work supervisors and various things associated with the waking hours make appearances, only here we are left to work out the rationale of their presence as the subconscious brain attempts to do when we sleep.

On my own in the space after the visitors have gone I like to stay and reflect on the conversations, minus the people but surrounded by the work, as a way to construct my writing around each exhibition. It is in these moments that things start to become clear in my own mind, not because it has solidified the thoughts that I had before the exhibition but precisely because of the reverse. The clarity has emerged through conversation, dialogue and the views expressed through the experience of others. I imagine this is what Proust means when he talks about understanding other people's view of the universe through art, this is the value inherent in the presentation of art for an audience. Even if production is a solitary process in the studio, tucked away out of sight out of mind, the process continues to expand as it is experienced by others. In this way I maintain the opinion that over fourteen years and more than sixty projects it feels like every exhibition has been a completely singular and unique experience.

Bruce Davies | November 2025