Neuland, Familiar Longing: Griet Beyeart & Silvia Liebig’s ‘Junction’

By Amy Kitchingman

If there is one driving force behind BasementArtsProject, it is the desire to link contemporary art to an unconventional and sharply drawn sense of place. A guest at Bruce Davies’ gallery not only gets to engage with the work of the exhibiting artist, but with a family home, one which extends a welcoming, warm hand to those who visit. Nestled within a terraced house in South Leeds and a world away from the sterility of the White Cube, a vibrant creative environment emerges.

Work Rest & Play: Relaxing between jobs during installation in the garden of BasementArtsProject

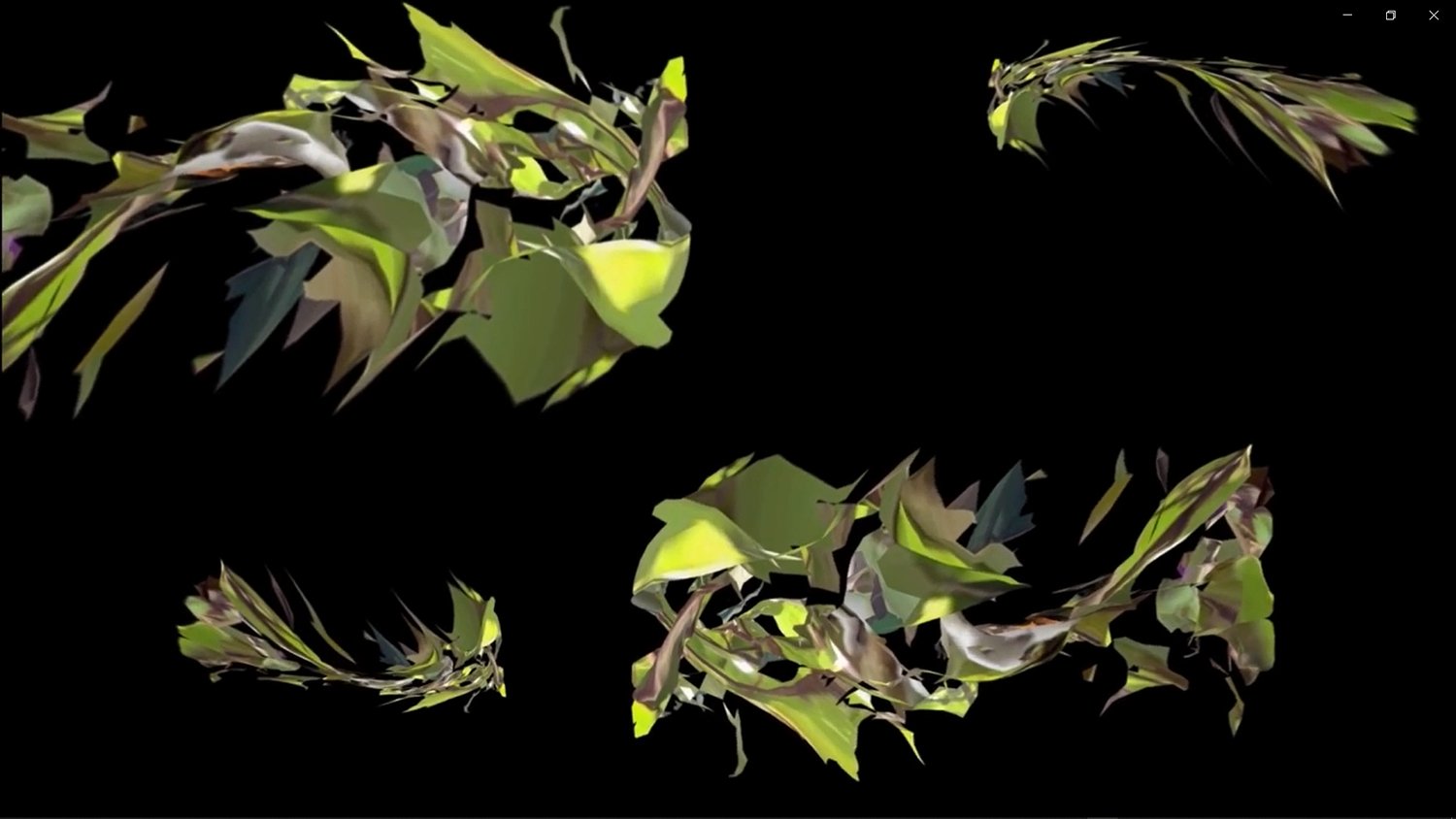

Place was perhaps the key theme underpinning Griet Beyeart and Silvia Liebig’s 2023 exhibition, ‘Junction’. Consisting of an installation and video art, with an aural landscape created by Beyeart, the exhibition was part of Liebig’s ongoing ‘Neuland’ project. In her own words, Neuland ‘explores aspects of places and narratives, linking knowledge about a place with associations and whimsical ideas’. ‘Junction’ moved into a more specific location, that of the "Allotment Garden". Liebig explained to me that she sees this place ‘as a self-contained, parallel universe with its own territory and its own rules.’

To many, an allotment garden is simultaneously meditative and generative. The ritual of planting requires a conscientious, careful action from a person, lest they risk unsatisfying results. Focus in the present is the deciding factor between a pathetic watery marrow or a beautiful dusky-orange squash in the future. For many, the profound focus of gardening provides a welcome escape from the stresses of everyday life, driven by a clear, fulfilling outcome.

In this sense, Liebig seems to provide a fresh interpretation of Foucault’s theory of the heterotopia. For Foucault, the heterotopia is a deliberately othered space. Roughly defined, it is a ‘counter-site’ which is linked to ‘slices in time’ and provides a specific ritualistic purpose in the lives of the people occupying it.[1] Liebig similarly spots a similar function within the allotment, describing it as a stopper in human evolution:

Thousands of years ago, people began a long journey through the infinite, dark and hostile universe. They had science and technology highly developed, but they could not find peace. So they chased with their allotments through infinity in search of a new home.

The allotment is a peaceful space, one which accompanies humanity amongst the frightening uncertainty of the wider universe. It also suggests possibility, as within its sanctuary, humanity can begin to search for a ‘new home’, one which embraces simplicity. Outside of the ceaselessness of the universe, is the allotment ‘slice of time’, defined by quiet, optimistic contemplation.

This is especially poignant to consider, when remembering that ‘Junction’ was initially disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic. BasementArtsProject, from our corner in Beeston, corresponded with Liebig at her home in Dortmund, in the hope that in-person work would be possible again soon. Beyeart was close by in Leeds, yet unable to visit us. It’s easy to imagine how alluring the allotment became for Liebig, in a time when even a small stroll outside became precious and pressurised. The ‘Junction’ we arrive at in this exhibition may be that of re-learning to appreciate various places once more, after our access was restricted for so long.

This sense of narrative also underpinned Beyeart’s creative process. For her soundscape, Beyeart initially used glass percussion and vocalisations, a common approach for her soundwork of that time, before layering strings and field recordings. These elements allowed her to express ‘the narrative in my head’. I asked Beyeart to describe the atmosphere she aimed to create:

[…] equally giving a sense of changing perspectives, of moving in and out of a place. There was an eeriness to the changing perspectives, the trolley and the play between the appearance of something real and the definite times where the space was not, which I wanted to emphasize.

There was certainly a sense of eeriness on entering ‘Junction’. This isn’t uncommon at BasementArts. After all, it holds a wet, metallic scent, deep in the pit of a Victorian terraced home. Thankfully the Davies family are upbeat enough to override that! Beyeart’s aural landscape, acknowledging that Liebig’s work slipped between ‘something real’ and otherworldly shapes, creates an inviting space within the unknown. As the visitor looked at unfamiliar objects, hearing mysterious yet familiar sounds, they were pulled inwards, forging meaning by closely examining the associations they made. ‘Junction’ invites the visitor to consider that the places they turn to for comfort may hold disturbing mysteries. However, this element of risk is precisely what makes the search for Neuland so exciting. Placing the enigmatic questions of existence within an allotment garden, one held spellbound by Beyeart’s soundscape, suggests that even the most commonplace of spaces holds the potential for creative discovery.

In terms of the technical assemblage of ‘Junction’, this exhibition continued a method I explored in my first essay for BasementArts, on a series of sculptures created by Jeffrey Knopf using 3D scans. This technology formed a key part of creating the exhibition’s main installation, as Liebig weaved experimental geometric motifs in wool over 3D scans of a garden shed. Liebig explained this process at length in our conversation:

The main motif of the installation, which is made up of individual sheets of paper approximately A5 in size, shows a 3D scan of a garden shed (a special type of hut in an allotment garden that can be found here in the Ruhr area). The yarn, which interweaves over different areas of this picture to form geometric polygonal shapes, is in a sense a structure, a principle with which I visualise the process of measurement.

When we are very young, we learn to estimate proportions and distances by using our fingers, feet and arms - our bodies - as units of measurement. Later, we have tools/instruments such as measuring rods and telescopes to use. A 3D scanner works by projecting light onto an object and capturing the reflection. It measures the time it takes for the light to return and thus determines the distance of each point. These points, represented as XYZ coordinates, are used together to digitally reconstruct the object in 3D.

Measuring seems to me to be a form of delimitation and even, in a certain sense, a way of taking possession of and ultimately ‘grasping’ an object.

By measuring the depicted object - in my case a garden - with the net of threads, I try not only to measure and grasp the real place/the real object, but also the various levels of interpretation and narratives with which these places in particular are charged.

Liebig poses a concept of measurement which cuts through my earlier proposition. If the allotment opens a playful space, through which we can consider the mysteries of existence, then measuring provides a means of ‘grasping’ something more concrete. Liebig’s link to childhood here is important. She conjures images of children jumping between blocks on the pavement, with each moment of enjoyment determined in the space between concrete lines. Before a ruler is available, children’s creativity can be even more ad-hoc, and completely unbound by the specificity of measurement. A portrait of themselves has an enormous, rotund head, a tiny body, and an accompanying dog as big as them. In childhood, these tentative attempts to understand space form the beginnings of our relationship with the wider world.

As Liebig points out, in adulthood, she is granted access to sophisticated tools like a 3D scanner. Here, modern technology can replicate an object through coordinates, using science to do what in a children’s story is achieved with the wave of a magic wand. Measuring then, rather than a limiting presence, is a means of ‘grasping’ stability. It provides a starting point, through which we can make sense of the real. For Liebig, this is the beginning of a process of interpretation, with no clear end, in which an artist can unravel the endless narratives a space might hold.

This was certainly a feeling I experienced when installing Liebig’s work, both at BasementArts and at a retrospective at Paradise Works in Manchester, which included numerous works by exhibiting artists at Basement. Assemblage of the work began with hammering nails into a series of points, before weaving wool around them until I recreated geometric shapes which Liebig had printed over her scans of a garden shed. Here, I closely followed a pre-established pattern, yet felt I’d experienced a process of discovery, if only in the act of transforming an unassuming ball of wool into a sophisticated polygonal web. Much like the stories I read as a child, where pirates would follow a map in pursuit of a chest of treasure, the route to my desired result held surprises I couldn’t have anticipated. This assembly process was deeply tied to Liebig and Beyeart’s aim to shift between various perspectives, as at one moment I felt thoroughly guided and at another left to puzzle out new interpretations of this existing framework. In every aspect of ‘Junction’, participants are taken on a journey, encouraged to embrace the uncertainty of Neuland.

One year on from ‘Junction’, BasementArtsProject finds itself uncovering Neuland within its local area of Beeston. Our current funding bids aim to install a mural by Chloe Harris and sculpture by Annabelle Richmond-Wright, to turn a neglected traffic junction into a ‘cultural gateway’, where people in an impoverished corner of the city can enjoy art at their leisure. The possibility of Neuland is perhaps the beauty of DIY art spaces, where we are not obliged to answer to past notions of institutional prestige as we reconfigure our chosen places. Moving forward, we would do well to recall the themes captured by Liebig and Beyeart. Although this search might take us to the unfamiliar, leave us desperate for the comfort of the real, these shifting states provide us with the creative impetus we need to discover the new.

[1]Michel Foucault, ‘Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias’, trans. by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité, 1984, 1-9, p.3, p.6.

Amy Kitchingman